The crisis in Iraq is tectonically important. Fighting between the

Iraqi government and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (or, as

it's abbreviated, ISIS) is tearing Iraq apart. The conflict has the

potential to transform the politics of the broader Middle East.

It's also extremely complicated. So we've broken down the 11 most important things you need to know to understand the issue, starting from the beginning.

ISIS is, in a roundabout way, a product of the Iraq war.

It's essentially a rebooted version of al-Qaeda in Iraq, the Islamist group that rose to power after the American invasion. US troops and allied Sunni militias defeated AQI during the post-2006 "surge," but it didn't demolish them. The US commander in Iraq, General Ray Odierno, described the group in 2010 as down but "fundamentally the same." "What they want," the general continued, "is to form an ungoverned territory or at least pieces of ungoverned territory, inside of Iraq, that they can take advantage of."

In 2011, the group rebooted. ISIS successfully freed a number of prisoners held by the Iraqi government and, slowly but surely, began rebuilding their strength. The chaos today is a direct result of the Iraqi government's failure to stop them.

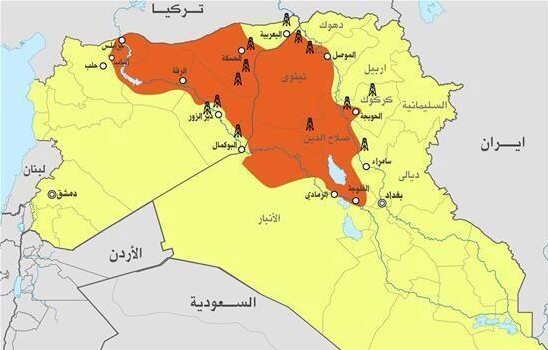

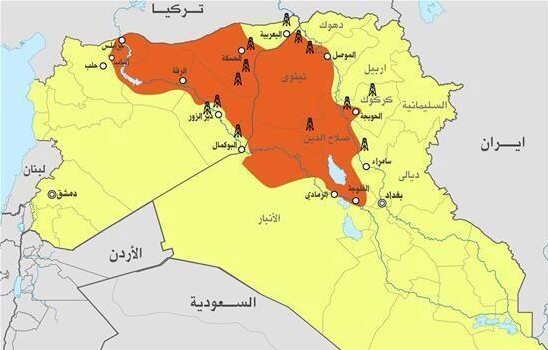

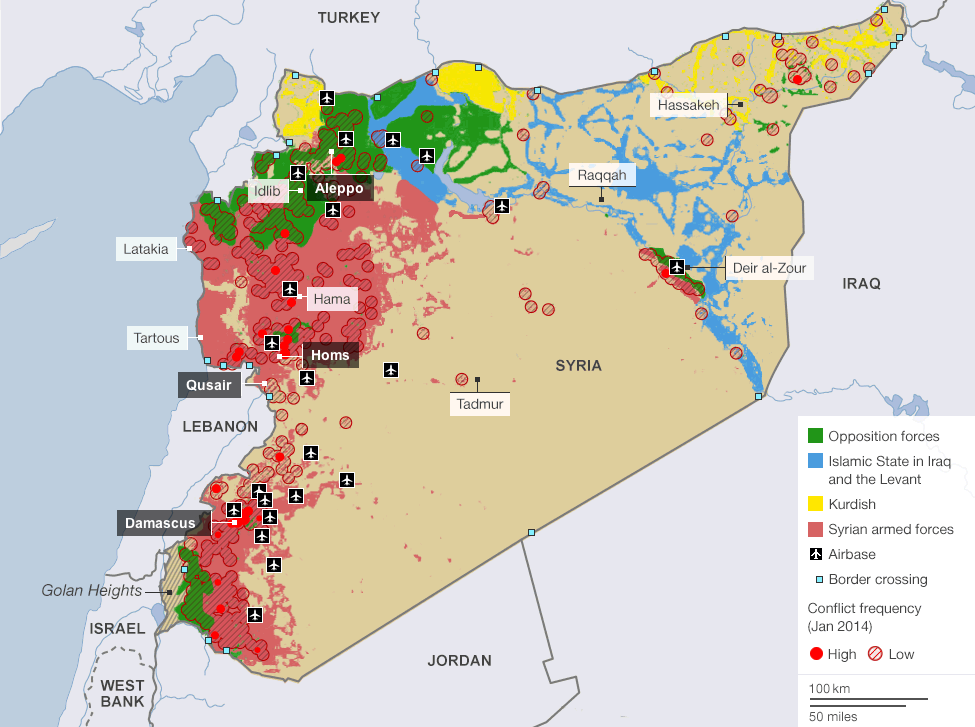

Today, ISIS holds a fair amount of territory in both Iraq and Syria — a mass roughly the size of Belgium. One ISIS map, from 2006, shows its ambitions stopping there — though interestingly overlapping a lot of oil fields:

Another shows their ambitions stretching across the Middle East, and some have apparently even included territory in North Africa:

Now, they have no chance of accomplishing any of these things in the foreseeable future. ISIS isn't even strong enough to topple the Iraqi or Syrian governments at present. But these maps do tell us something important about ISIS: they're incredibly ambitious, they think ahead, and they're quite serious about their expansionist Islamist ideology.

Perhaps the single most important factor in ISIS' recent resurgence is the conflict between Iraqi Shias and Iraqi Sunnis. ISIS fighters themselves are Sunnis, and the tension between the two groups is a powerful recruiting tool for ISIS.

The difference between the two largest Muslim groups originated with a controversy over who got to take power after the Prophet Muhammed's death, which you can read all about here. But Iraq's sectarian problems aren't about relitigating 7th century disputes; they're about modern political power and grievances.

A majority of Iraqis are Shias, but Sunnis ran the show when Saddam Hussein, himself Sunni, ruled Iraq. The civil war after the American invasion had a brutally sectarian cast to it, and the pseudo-democracy that emerged afterwards empowered the Shia majority (with some heavy-handed help from Washington). The point is that the two groups don't trust each other, and so far have competed in a zero-sum game for control over Iraqi political institutions.

So long as Shias control the government, and Sunnis don't feel like they're fairly represented, ISIS has an audience for its radical Sunni message. That's why ISIS is gaining in the heavily Sunni northwest.

When ISIS reestablished itself, it put Sunni sectarianism at the heart of its identity and propaganda. The government persecution, according to the Washington Institute for Near East Studies' Michael Knights, "played right into their hands." Maliki "made all the ISIS propaganda real, accurate." That made it much, much easier for ISIS to replenish its fighting stock.

That wasn't the only way the Iraqi government helped ISIS grow, according to Knights. The US and Iraqi governments released a huge number of al-Qaeda prisoners from jail, which he thinks called "an unprecedented infusion of skilled, networked terrorist manpower - an infusion at a scale the world has never seen." US forces were running sophisticated raids "every single night of the year," and Knights believes their withdrawal gave ISIS a bit more breathing room.

Iraqi Kurdistan in northeast Iraq is governed semi-autonomously. The Kurdish security forces are partly integrated with the government, but there's somewhere between 80,000 and 240,000 Kurdish peshmerga (militias) who don't answer to Baghdad. They're well equipped and trained, and represent a serious military threat to ISIS.

You'll notice that Mosul is inside the dotted lines of territory under defacto Kurdish control. Indeed, according to Knights, Kurdish security forces control eastern parts of the city. More broadly, Iraqi Kurdistan borders ISIS territory at a number of different points.

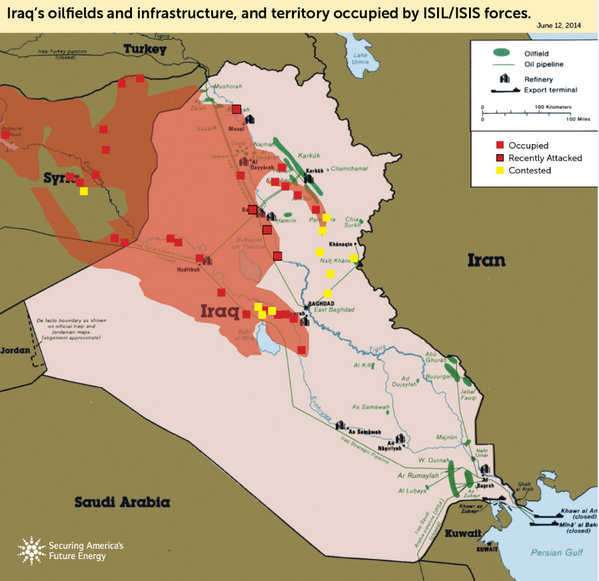

So far, there hasn't been any major conflict between the Kurds and ISIS. The Kurds have taken advantage of the chaos to occupy Kirkuk, a city near massive oil deposits that they've wanted for some time. That means the crisis has been, in a strange way, a boon to the Kurds — provided that they can remain out of the fighting.

The chaos in Syria allowed ISIS to hold this territory pretty securely. This is a big deal in terms of weaponry and money. "The war gave them a lot of access to heavy weaponry," Michael Knights said. ISIS also "has a funding stream available to them because of local businesses and the oil and gas sector."

It's also hugely important as a safe zone. When fighting Syrian troops, ISIS can safely retreat to Iraq; when fighting Iraqis it can go to Syria. Statistical evidence says these safe "rear areas" help insurgents win: "one of the best predictors of insurgent success that we have to date is the presence of a rear area," Jason Lyall, a political scientist at Yale University who studies insurgencies, said.

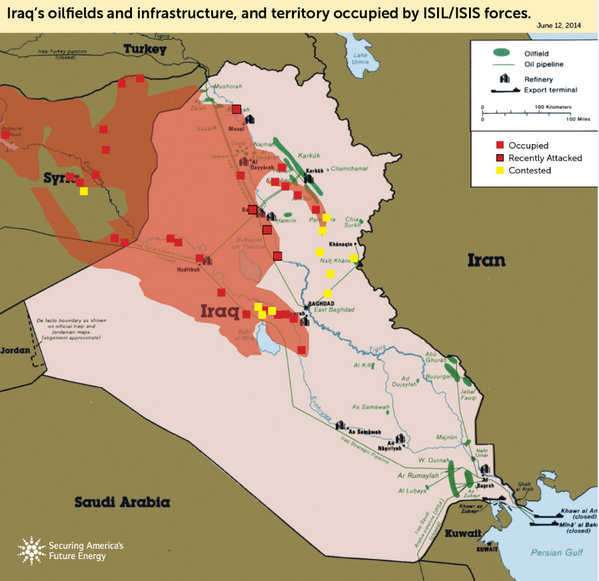

As Brad Plumer explains elsewhere on Vox, ISIS' gains threaten one important oil pipeline that ships to Turkey, but not the broader oil infrastructure. Right now, then, ISIS controls a significant part of Iraq's territory, but hasn't yet majorly threatened the industry that makes up 95 percent of Iraq's GDP.

The Iranian government is Shia, and it has close ties with the Iraqi government. Much like in Syria, Iran doesn't want Sunni Islamist rebels to topple a friendly Shia government. So in both countries, Iran has gone to war.

Iran has sent two battalions of Iranian Revolutionary Guards to help Iraq fight ISIS. These aren't just any old Iranian troops. They're Quds Force, the Guards' elite special operations group. The Quds Force is one of the most effective military forces in the Middle East, a far cry from the undisciplined and disorganized Iraqi forces that fled from a much smaller ISIS force in Mosul. One former CIA officer called Quds Force commander Qassem Suleimani "the single most powerful operative in the Middle East today." Suleimani, the Journal reports, is currently helping the Iraqi government "manage the crisis" in Baghdad.

These Iranian troops outclass ISIS on the battlefield. According to the Wall Street Journal, combined Iranian-Iraqi forces have already retaken about 85 percent of Tikrit. That alone demonstrates the military significance of Iranian intervention: Iraqi forces have previously floundered in block-to-block city battles with ISIS.

However, Iranian intervention could also help ISIS in its quest to build support among Iraq's Sunnis. The perception that the Iraqi government is far too close to Iran is already a significant grievance among Sunnis. That's part pure sectarianism and part nationalism. Many Iraqis don't like the idea of a foreign power manipulating their government, particularly Iran (memories of the Iran-Iraq war haven't faded).

So Iranian participation in actual combat risks legitimizing ISIS' propaganda line: this isn't a conflict between the central Iraqi government and Islamist rebels, but rather a war between Sunnis and Shias.

Here's one other scary thought. Iran is now helping both the Iraqi and Syrian governments fight largely Sunni rebels. What happens if the two battlefields get joined?

ISIS cannot challenge the Iraqi government for control over the country. On a basic level, it's simple math. A rough count of ISIS' fighting strength suggests it has a bit more than 7,000 combat troops, and it can occasionally grab reinforcements from other extremist militias. The Iraqi army has 250,000 troops, plus armed police. That Iraqi military also has tanks, airplanes, and helicopters. ISIS can't make a serious play for the control of Baghdad, let alone the south of Iraq, without a serious risk of getting crushed.

But the Iraqi army is also a total mess, which explains why ISIS has had the success it's had despite being dramatically outnumbered.

Take ISIS' victory in Mosul. 30,000 Iraqi troops ran from 800 ISIS fighters. Those are 40:1 odds! Yet Iraqi troops ran because they simply didn't want to fight and die for this government. There had been hundreds of desertions per month for months prior to the events of June 10th. The escalation with ISIS is, of course, making it worse.

Sectarianism also plays a role here. The Iraqi army is mixed Sunni-Shia, and "it appears that the Iraqi Army is cleaving along sectarian lines," Yale's Jason Lyall said. "The willingness of Sunni soldiers to fight to retake Mosul appears limited." This makes some sense out of the Mosul rout: some Sunni Muslims don't really want to fight other Sunnis in the name of a government that oppresses them.

This suggests a natural limit to ISIS' expansion. Mosul is a mostly Sunni city, but military resistance will be much stiffer in Shia areas. ISIS needs to stick to Sunni land if it doesn't want to overreach.

Multiple reports say the Iraqi government has quietly requested American military aid in the form of drone strikes against ISIS. Let's assume those are correct. Will Obama say yes?

That's not 100 percent clear. So far, there's no evidence that the administration is leaning towards strikes. But in a press conference about Iraq, Obama didn't rule them out.

There are lots of competing incentives for the president on this issue. His administration has always touted withdrawal from Iraq as a major accomplishment, but it also (rightly or wrongly) sees drone strikes as a highly effective way of fighting extremist groups like ISIS. The administration is skittish about siding with a repressive creep like Maliki, but it has already publicly committed to assisting the Iraqi army in as-yet unannounced ways.

There's also a growing political debate over whether the Obama administration deserves blame for the chaos. Some conservative critics say Obama should have convinced Iraq to allow him to leave a residual force of American troops to conduct raids on ISIS. The administration's defenders say that would have been impossible, and probably wouldn't have prevented this regardless.

So, to recap. Iraq has essentially just began another civil war, and it's totally unclear how long it's going to last or how it's going to end. And no one's sure what to do about it.

It's also extremely complicated. So we've broken down the 11 most important things you need to know to understand the issue, starting from the beginning.

1. ISIS used to be called al-Qaeda in Iraq

ISIS is, in a roundabout way, a product of the Iraq war.

It's essentially a rebooted version of al-Qaeda in Iraq, the Islamist group that rose to power after the American invasion. US troops and allied Sunni militias defeated AQI during the post-2006 "surge," but it didn't demolish them. The US commander in Iraq, General Ray Odierno, described the group in 2010 as down but "fundamentally the same." "What they want," the general continued, "is to form an ungoverned territory or at least pieces of ungoverned territory, inside of Iraq, that they can take advantage of."

In 2011, the group rebooted. ISIS successfully freed a number of prisoners held by the Iraqi government and, slowly but surely, began rebuilding their strength. The chaos today is a direct result of the Iraqi government's failure to stop them.

2. ISIS wants to carve out an Islamic state in Iraq and Syria

Their goal since being founded in 2004 has been remarkably consistent: found a hardline Sunni Islamic state. General Odierno again: "They want complete failure of the government in Iraq. They want to establish a caliphate in Iraq." Even after ISIS split with al-Qaeda in February 2014 (in large part because ISIS was too brutal even for al-Qaeda), ISIS' goal remained the same.Today, ISIS holds a fair amount of territory in both Iraq and Syria — a mass roughly the size of Belgium. One ISIS map, from 2006, shows its ambitions stopping there — though interestingly overlapping a lot of oil fields:

Another shows their ambitions stretching across the Middle East, and some have apparently even included territory in North Africa:

Now, they have no chance of accomplishing any of these things in the foreseeable future. ISIS isn't even strong enough to topple the Iraqi or Syrian governments at present. But these maps do tell us something important about ISIS: they're incredibly ambitious, they think ahead, and they're quite serious about their expansionist Islamist ideology.

3. ISIS thrives on tension between Iraq's two largest religious groups

Perhaps the single most important factor in ISIS' recent resurgence is the conflict between Iraqi Shias and Iraqi Sunnis. ISIS fighters themselves are Sunnis, and the tension between the two groups is a powerful recruiting tool for ISIS.

The difference between the two largest Muslim groups originated with a controversy over who got to take power after the Prophet Muhammed's death, which you can read all about here. But Iraq's sectarian problems aren't about relitigating 7th century disputes; they're about modern political power and grievances.

A majority of Iraqis are Shias, but Sunnis ran the show when Saddam Hussein, himself Sunni, ruled Iraq. The civil war after the American invasion had a brutally sectarian cast to it, and the pseudo-democracy that emerged afterwards empowered the Shia majority (with some heavy-handed help from Washington). The point is that the two groups don't trust each other, and so far have competed in a zero-sum game for control over Iraqi political institutions.

So long as Shias control the government, and Sunnis don't feel like they're fairly represented, ISIS has an audience for its radical Sunni message. That's why ISIS is gaining in the heavily Sunni northwest.

4. The Iraqi government has made this tension worse by persecuting Sunnis and through other missteps

Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, a Shia Muslim, has built a Shia sectarian state and refused to take steps to accommodate Sunnis. Police have killed peaceful Sunni protestors and used anti-terrorism laws to mass-arrest Sunni civilians. ISIS cannily exploited that brutality to recruit new fighters.When ISIS reestablished itself, it put Sunni sectarianism at the heart of its identity and propaganda

When ISIS reestablished itself, it put Sunni sectarianism at the heart of its identity and propaganda. The government persecution, according to the Washington Institute for Near East Studies' Michael Knights, "played right into their hands." Maliki "made all the ISIS propaganda real, accurate." That made it much, much easier for ISIS to replenish its fighting stock.

That wasn't the only way the Iraqi government helped ISIS grow, according to Knights. The US and Iraqi governments released a huge number of al-Qaeda prisoners from jail, which he thinks called "an unprecedented infusion of skilled, networked terrorist manpower - an infusion at a scale the world has never seen." US forces were running sophisticated raids "every single night of the year," and Knights believes their withdrawal gave ISIS a bit more breathing room.

5. ISIS raises money like a government

This money goes a long way: it pays better salaries than moderate Syrian rebels or the Syrian and Iraqi professional militaries, both of which have suffered mass desertions. ISIS also appears to enjoy better internal cohesion than any of its state or non-state enemies, at least for the moment.Second, it makes the idea that ISIS' near-term goal is to hold Iraqi oil and power facilities more credible. Some reports suggest they've restarted oil fields in eastern Syria. If that's true, then ISIS isn't just a strong military force: they're also smartly laying the economic groundwork to accomplish their dream of an Islamic state in Iraq and Syria.

6. Iraq has another major ethno-religious group, the Kurds, who could matter in this fight

Kurds are mostly Sunnis, but they're ethnically distinct from Iraqi Arabs. They control a swath of northeast Iraq where a lot of the oil fields lie, and are something of a wild card in the conflict between the Iraqi government and ISIS.

Iraqi Kurdistan in northeast Iraq is governed semi-autonomously. The Kurdish security forces are partly integrated with the government, but there's somewhere between 80,000 and 240,000 Kurdish peshmerga (militias) who don't answer to Baghdad. They're well equipped and trained, and represent a serious military threat to ISIS.

You'll notice that Mosul is inside the dotted lines of territory under defacto Kurdish control. Indeed, according to Knights, Kurdish security forces control eastern parts of the city. More broadly, Iraqi Kurdistan borders ISIS territory at a number of different points.

So far, there hasn't been any major conflict between the Kurds and ISIS. The Kurds have taken advantage of the chaos to occupy Kirkuk, a city near massive oil deposits that they've wanted for some time. That means the crisis has been, in a strange way, a boon to the Kurds — provided that they can remain out of the fighting.

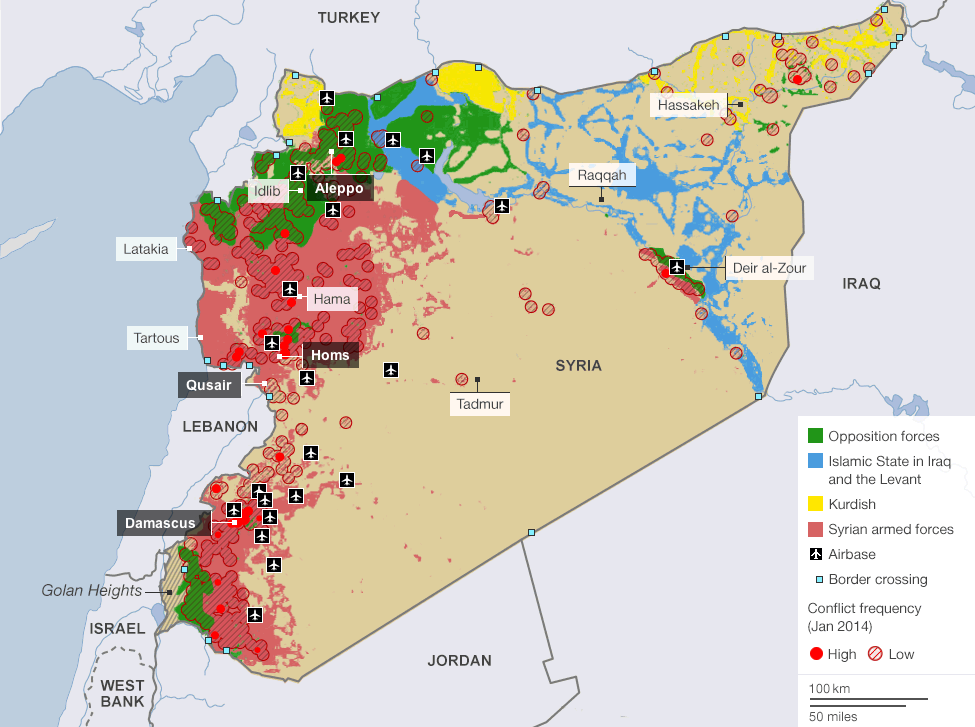

7. The Syria conflict has made ISIS much stronger

The crisis in Syria is one of the most important reasons why ISIS grew capable of mounting such an effective attack on the Iraqi government. To see why, take a look at this map from March, paying special attention to the blue ISIS-controlled areas in eastern Syria:

The chaos in Syria allowed ISIS to hold this territory pretty securely. This is a big deal in terms of weaponry and money. "The war gave them a lot of access to heavy weaponry," Michael Knights said. ISIS also "has a funding stream available to them because of local businesses and the oil and gas sector."

It's also hugely important as a safe zone. When fighting Syrian troops, ISIS can safely retreat to Iraq; when fighting Iraqis it can go to Syria. Statistical evidence says these safe "rear areas" help insurgents win: "one of the best predictors of insurgent success that we have to date is the presence of a rear area," Jason Lyall, a political scientist at Yale University who studies insurgencies, said.

8. Mosul, the big city ISIS recently conquered, is really important — and ISIS has spread out from there

Mosul is the second-largest city in Iraq, second only to Baghdad. It's the capital of the northwester Ninevah province, and fairly close to major oilfields. The Mosul Dam, according to McClatchy, plays an important role in the country's water supply. ISIS conquered most of Mosul on June 10th, and it's unclear when the Iraqi army will make a serious play to take it back.

As Brad Plumer explains elsewhere on Vox, ISIS' gains threaten one important oil pipeline that ships to Turkey, but not the broader oil infrastructure. Right now, then, ISIS controls a significant part of Iraq's territory, but hasn't yet majorly threatened the industry that makes up 95 percent of Iraq's GDP.

9. Iran is already involved, and this conflict could get much bigger

The Iranian government is Shia, and it has close ties with the Iraqi government. Much like in Syria, Iran doesn't want Sunni Islamist rebels to topple a friendly Shia government. So in both countries, Iran has gone to war.

These Iranian troops outclass ISIS on the battlefield

Iran has sent two battalions of Iranian Revolutionary Guards to help Iraq fight ISIS. These aren't just any old Iranian troops. They're Quds Force, the Guards' elite special operations group. The Quds Force is one of the most effective military forces in the Middle East, a far cry from the undisciplined and disorganized Iraqi forces that fled from a much smaller ISIS force in Mosul. One former CIA officer called Quds Force commander Qassem Suleimani "the single most powerful operative in the Middle East today." Suleimani, the Journal reports, is currently helping the Iraqi government "manage the crisis" in Baghdad.

These Iranian troops outclass ISIS on the battlefield. According to the Wall Street Journal, combined Iranian-Iraqi forces have already retaken about 85 percent of Tikrit. That alone demonstrates the military significance of Iranian intervention: Iraqi forces have previously floundered in block-to-block city battles with ISIS.

Iranian intervention could also help ISIS in its quest to build support among Iraq's Sunnis

However, Iranian intervention could also help ISIS in its quest to build support among Iraq's Sunnis. The perception that the Iraqi government is far too close to Iran is already a significant grievance among Sunnis. That's part pure sectarianism and part nationalism. Many Iraqis don't like the idea of a foreign power manipulating their government, particularly Iran (memories of the Iran-Iraq war haven't faded).

So Iranian participation in actual combat risks legitimizing ISIS' propaganda line: this isn't a conflict between the central Iraqi government and Islamist rebels, but rather a war between Sunnis and Shias.

Here's one other scary thought. Iran is now helping both the Iraqi and Syrian governments fight largely Sunni rebels. What happens if the two battlefields get joined?

10. The Iraqi Army is much larger than ISIS, but also a total mess

ISIS cannot challenge the Iraqi government for control over the country. On a basic level, it's simple math. A rough count of ISIS' fighting strength suggests it has a bit more than 7,000 combat troops, and it can occasionally grab reinforcements from other extremist militias. The Iraqi army has 250,000 troops, plus armed police. That Iraqi military also has tanks, airplanes, and helicopters. ISIS can't make a serious play for the control of Baghdad, let alone the south of Iraq, without a serious risk of getting crushed.

But the Iraqi army is also a total mess, which explains why ISIS has had the success it's had despite being dramatically outnumbered.

Take ISIS' victory in Mosul: 30,000 Iraqi troops ran from 800 ISIS fighters

Take ISIS' victory in Mosul. 30,000 Iraqi troops ran from 800 ISIS fighters. Those are 40:1 odds! Yet Iraqi troops ran because they simply didn't want to fight and die for this government. There had been hundreds of desertions per month for months prior to the events of June 10th. The escalation with ISIS is, of course, making it worse.

Sectarianism also plays a role here. The Iraqi army is mixed Sunni-Shia, and "it appears that the Iraqi Army is cleaving along sectarian lines," Yale's Jason Lyall said. "The willingness of Sunni soldiers to fight to retake Mosul appears limited." This makes some sense out of the Mosul rout: some Sunni Muslims don't really want to fight other Sunnis in the name of a government that oppresses them.

This suggests a natural limit to ISIS' expansion. Mosul is a mostly Sunni city, but military resistance will be much stiffer in Shia areas. ISIS needs to stick to Sunni land if it doesn't want to overreach.

11. Iraq may secretly want American drone strikes, and Obama may be considering them

Multiple reports say the Iraqi government has quietly requested American military aid in the form of drone strikes against ISIS. Let's assume those are correct. Will Obama say yes?

That's not 100 percent clear. So far, there's no evidence that the administration is leaning towards strikes. But in a press conference about Iraq, Obama didn't rule them out.

There's a growing political debate over whether the Obama administration deserves blame for the chaos

There are lots of competing incentives for the president on this issue. His administration has always touted withdrawal from Iraq as a major accomplishment, but it also (rightly or wrongly) sees drone strikes as a highly effective way of fighting extremist groups like ISIS. The administration is skittish about siding with a repressive creep like Maliki, but it has already publicly committed to assisting the Iraqi army in as-yet unannounced ways.

There's also a growing political debate over whether the Obama administration deserves blame for the chaos. Some conservative critics say Obama should have convinced Iraq to allow him to leave a residual force of American troops to conduct raids on ISIS. The administration's defenders say that would have been impossible, and probably wouldn't have prevented this regardless.

So, to recap. Iraq has essentially just began another civil war, and it's totally unclear how long it's going to last or how it's going to end. And no one's sure what to do about it.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

The crisis in Iraq is tectonically important. Fighting between the Iraqi government and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant

ReplyDelete